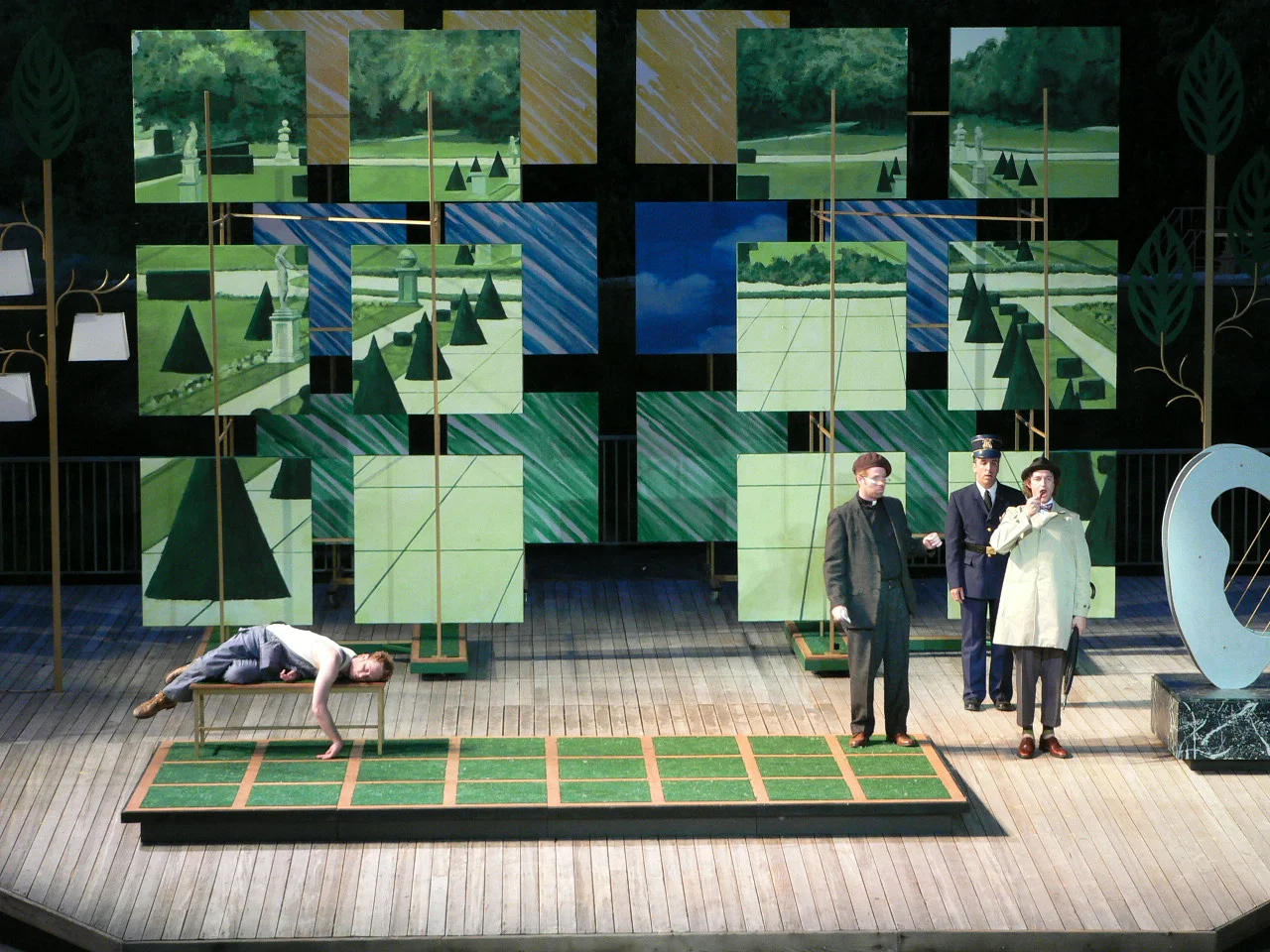

LOVE'S LABOR'S LOST

Set Design: Russell Metheny | Lighting Design: Rick Martin

Costume Design: Kim Krumm Sorenson | Sound Design: Seth Asa Sengel with Peter John Still

Scroll down to read Drew's director's note for Love's Labor's Lost at Idaho Shakespeare Festival and Great Lakes Theater.

Love's Labor's Lost by William Shakespeare | Director's Note

“The work of art must make reality more real.” —Yvan Goll (1891 - 1959)

There lies a paradox at the heart of Love’s Labor’s Lost: In what at first appears to be his most time bound play, intended perhaps as a satire of courtly life during the reign of Elizabeth I, Shakespeare creates a fanciful world of eloquence and artifice, seemingly far-removed from the facts of everyday life. Yet in this world of kings, princesses, and visitors from far-off lands, we get a strong impression of how ordinary lives are lived. People come and go. They proclaim, they negotiate, they joke and gibe, and they flirt, all the while hoping that the world will see them as they wish to see themselves.

Assumed to be an early work, the play disappeared from production for more than two hundred years after Shakespeare’s time and has only found its real footing on the stage within the last century. Early critics found little to appreciate in it; Hazlitt went so far as to advocate its removal from the canon. Yet from its first production in the twentieth century, modern audiences have relished its “great feast of language,” its sharply drawn characters, and its refreshingly simple plot.

Compared to the often elaborately compelling stories of Shakespeare’s other plays, the tale told in Love’s Labor’s Lost has a decidedly convenient, if not downright coincidental, feel to it. Oaths are sworn; complications arise; the plot turns on characters’ seemingly arbitrary entrances and exits. And through it all they talk. And talk and talk: in prose, in verse, in rhyme, in Latin, in nonsense syllables and snatches of old songs. The flood of language seems likely to drown speaker and audience alike. Yet Navarre’s King Ferdinand, his lords and subjects, and their guests from France frolic happily in the streams of words and their ever-shifting meanings. Indeed, at times the characters seem punch-drunk on the stuff; the very act of speaking threatens to trump what is being said. Perhaps Shakespeare wasn’t all that interested in resolving the burning questions of love in Navarre. (Ultimately, what is love but the slipperiest word of all?) Instead, Love’s Labor’s Lost, in all its verbal extravagance, considers how we experience the world and how we see ourselves in it. As John Berger wrote, “Seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world.” We see the world, and then we use language to communicate our experience, making sense (or not) of that world to ourselves and each other.

The abundant humanity of Love’s Labor’s Lost stems from our sensing what lies at the root of all the talk. We recognize that it is through language, with all its convolutions, that we connect to each other individually and as a society. Speech allows us to reach out from deep within ourselves and express our feelings, our aspirations, our dreams, our fears. At the start of the play, the king and his men set out on a quest of admirable, if fanatical, integrity: to know that which is yet unknown about the world. Their mission, diverted at once by the appearance of the princess and her retinue, sends them out of a rarified world of intellectual absolutes into a poetic realm of impulsive inspiration, where hard-to-articulate thoughts and feelings reign supreme.

Caught up as it is in frivolous play, verbal high jinks, and overblown passion, Love’s Labor’s Lost leads its characters and audience into the very dark center of life’s great mysteries. Shakespeare gives us no simple answers, but urges us to find comfort, if not meaning, in our connections to people and in the simple, tangible realities around us. If we gain nothing else from this nearly ‘lost’ comedy, we learn how to celebrate all that is marvelous in the unknown—and, indeed, the unknowable.

-Drew Barr