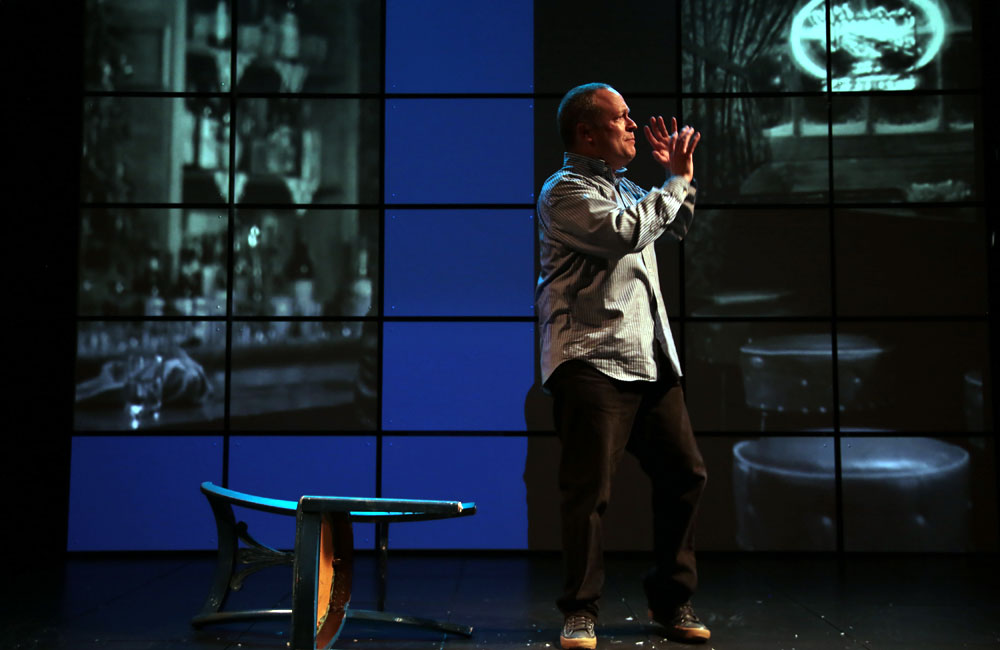

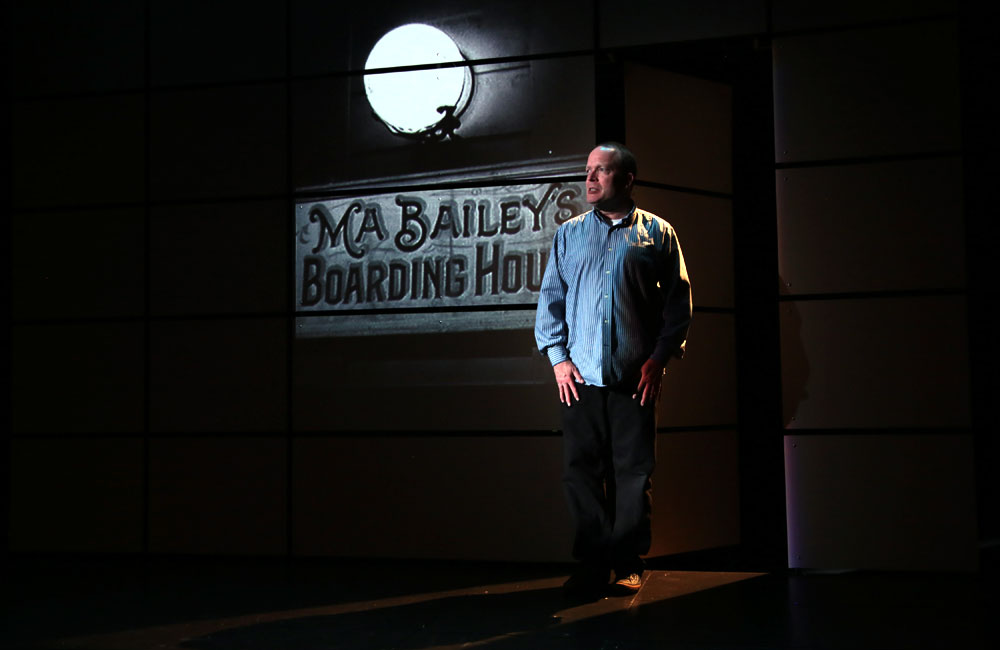

THIS WONDERFUL LIFE

Set Design: Rick Martin | Lighting Design: Rick Martin

Sound Design: Peter John Still | Projection Design: Rick Martin

Scroll down to read Drew's director's note for This Wonderful Life at Boise Contemporary Theater.

This Wonderful Life | Director's Note

“Memory is never a precise duplicate of the original... it is a continuing act of creation.”

--Rosalind Cartwright, The Twenty-Four Hour Mind

Have you ever seen Frank Capra’s film It’s A Wonderful Life? (Believe it or not, there are people who haven’t.) How well do you remember it? Are your memories tied to a specific place or time of viewing? Do they hinge on the story or on aspects of the filmmaking--the cast, say, or that business with Zuzu's petals? If you haven’t seen the movie, what do you know of it, and how does that information create an idea in your mind? Perhaps it evokes an opinion so certain and powerful that it almost makes you feel like you have seen Capra's 1946 holiday classic. But remember, you haven’t.

How do we remember what we remember and, more importantly, why? The science of remembering, which traces its study at least as far back as the fifth century B.C. when the Greek poet Simonides’ invented a technique known as the “art of memory,” continues to compel scientists, psychologists, and artists to this day. In The Book of Memory, Mary Carruthers writes, “Ancient and medieval people reserved their awe for memory. Their greatest geniuses they describe as people of superior memories.” Forever confronted by the mysteries of the mind and the tricks it can play, we’ve invented ever-more capable tools to bolster unreliable memory and keep it from failing us. And as we depend more and more on these external devices, our relationship to the act and art of remembering inevitably changes.

Then there are actors, who must possess superbly elastic memories in order to practice their craft on even the most rudimentary level. With every role, an actor memorizes a text, as well as a series of physical actions. Committing both to memory typically requires weeks of intense effort, along with mind- and body-numbing repetition. And that's when the really hard part begins, for then the actor must, in essence, forget it all—every word and gesture that he or she has worked so arduously to "lock in"—so that night after night, in our presence, it can be remembered afresh. It is in this re-remembering that actors engage our hearts and minds. Our presence fundamentally changes what the actor knows and remembers, just as the actor's ritual recreation of their experience compels our participation. In this collective re-imagining of a story (familiar or not), new memories are made. And something we thought of as fixed and separate from ourselves becomes, indelibly, a part of us.

Welcome to Bedford Falls. It’s just like you remembered. Isn’t it?

-Drew Barr